Religion and Conflict Across the Globe: Is There a Remedy?

Religion and Conflict Across the Globe: Is There a Remedy? on ICERM Radio aired on Thursday, September 15, 2016 @ 2 PM Eastern Time (New York).

ICERM Lecture Series

Theme: “Religion and Conflict Across the Globe: Is There a Remedy?”

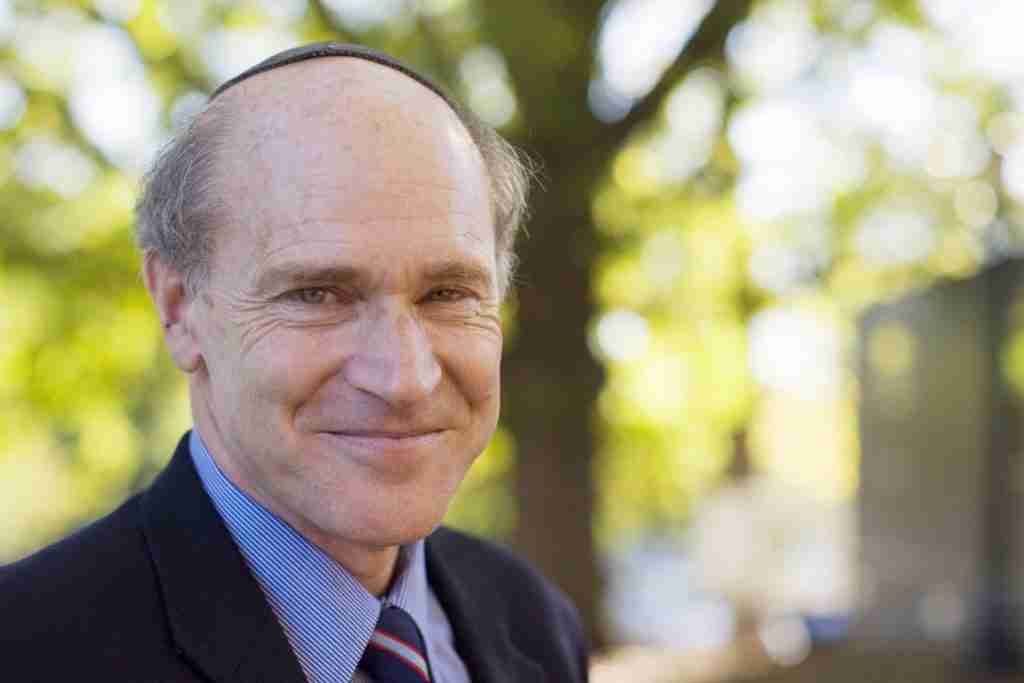

Guest Lecturer: Peter Ochs, Ph.D., Edgar Bronfman Professor of Modern Judaic Studies at the University of Virginia; and Cofounder of the (Abrahamic) Society for Scriptural Reasoning and the Global Covenant of Religions (an NGO devoted to engaging governmental, religious, and civil society agencies in comprehensive approaches to reducing religion-related violent conflicts).

Synopsis:

Recent news headlines seem to give secularists more courage to say “We told you so!” Is religion itself really dangerous to humankind? Or has it taken western diplomats too long to realize that religious groups do not necessarily act like other social groups: that there are religious resources for peace as well as conflict, that it takes special knowledge to understand religions, and that new coalitions of government and religious and civil society leaders are needed to engage religious groups in times of peace as well as conflict. This Lecture introduces the work of the “Global Covenant of Religions, Inc.,” a new NGO dedicated to drawing on religious as well as governmental and civil society resources to reduce religion-related violence….

Outline of Lecture

Introduction: Recent studies suggest that religion is indeed a significant factor in armed conflict around the world. I am going to speak with you audaciously. I will ask what seems like 2 impossible questions? And I will also claim to answer them: (a) Is religion itself really dangerous to humankind? I WILL answer Yes it is. (b) But is there any solution to religion -related violence? I WILL answer Yes there is. Furthermore, I shall have enough chutzpah to think that I can tell you what the solution is.

My lecture is organized into 6 major claims.

Claim #1: RELIGION has always been DANGEROUS because each religion has traditionally housed a means of granting individual human beings direct access to the deepest values of a given society. When I say this, I use the term “values” to refer to means of direct access to the rules of behavior and of identity and of relationship that hold a society together — and that therefore bind members of the society to each other.

Claim #2: My second claim is that RELIGION IS EVEN MORE DANGEROUS NOW, TODAY

There are many reasons Why, but I believe the strongest and deepest reason is that modern Western civilization has for centuries tried its hardest to undo the power of religions in our lives.

But why would the modern effort to weaken religion make religion more dangerous? The opposite should be the case! Here is my 5-step response:

- Religion did not go away.

- There has been a draining of brainpower and cultural energy away from the great religions of the West, and therefore away from careful nurturance of the deep sources of value that still lie there often un-attended at the foundations of Western civilization.

- That draining away took place not only in the West but also in the Third World nations colonized for 300 years by Western powers.

- After 300 years of colonialism, religion remains strong in the passion of its followers both East and West, but religion also remains underdeveloped through centuries of interrupted education, refinement, and care.

- My conclusion is that, when religious education and learning and teaching is underdeveloped and unrefined, then the societal values traditionally nurtured by the religions are underdeveloped and unrefined and members of religious groups behave badly when confronted by new challenges and change.

Claim #3: My third claim concerns why the world’s great powers have failed to resolve religion-related wars and violent conflict. Here are three bits of evidence about this failure.

- The Western foreign affairs community, including United Nations, has only very recently taken official note of the global increase in specifically religion-related violent conflict.

- An analysis offered by Jerry White, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State who oversaw a new Bureau of the State Department that focused on conflict reduction, in particular when it involved religions:…He argues that, through the sponsorship of these institutions, thousands of agencies now do good work in the field, caring for victims of religion -related conflicts and, in some cases, negotiating reductions in degrees of religion-related violence. He adds, however, that these institutions have had no overall success in stopping any single case of ongoing religion-related conflict.

- Despite the diminishment in state power in many parts of the world, the major Western governments still remain the single strongest agents of response to conflicts around the world. But the foreign policy leaders, researchers and agents and all these governments have inherited a centuries old assumption that the careful study of religions and religious communities is not a necessary tool for foreign policy research, policymaking, or negotiation.

Claim #4: My fourth claim is that the Solution requires a somewhat new concept of peace building. The concept is only “somewhat new,” because it is commonplace within many folk communities, and inside of many additional any religious group and other kinds of traditional groups. It is nonetheless “new,” because modern thinkers have tended to strip this commonplace wisdom away in favor of a few abstract principles that are useful, but only when reshaped to fit each different context of concrete peacebuilding. According to this new concept:

- We do not study “religion” in a general way as a general type of human experience….We study the way individual groups involved in a conflict practice their own local variety of a given religion. We do this by listening to members of these groups describe their religions in their own terms.

- What we mean by the study of religion is not merely a study of a particular local group’s deepest values; it is also a study of the way those values integrate their economic, political, and societal behavior. That is what was missing in political analyses of conflict up till now: attention to the values that coordinate all aspects of a group’s activity, and what we call “religion” refers to the languages and practices through which most local non-Western groups coordinate their values.

Claim #5: My fifth overall claim is that the program for a new international organization, “The Global Covenant of Religions,” illustrates how peacebuilders could apply this new concept to designing and implementing policies and strategies for resolving religion-related conflicts around the globe. The research goals of GCR are illustrated by the efforts of a new research initiative at the University of Virginia: Religion, Politics, and Conflict (RPC). RPC draws on the following premises:

- Comparative studies are the only means for observing patterns of religious behavior. Discipline-specific analyses, for example in economics or politics or even religious studies, do not detect such patterns. But, we have discovered that, when we compare the results of such analyses side by side, we can detect religion-specific phenomena that did not show up in any of the individual reports or data sets.

- It is almost all about language. Language is not just a source of meanings. It is also a source of social behavior or performance. Much of our work focuses on language studies of groups involved in religion-related conflict.

- Indigenous Religions: The most effective resources for identifying and repairing religion-related conflict must be drawn from out of the indigenous religious groups that are party to the conflict.

- Religion and Data Science: A part of our research program is computational. Some of the specialists, for example, in economics and politics, employ computational tools to identify their specific regions of information. We also need the assistance of data scientists for building our overall explanatory models.

- “Hearth-to-Hearth” Value Studies: Against Enlightenment assumptions, the strongest resources for repairing inter-religious conflict lie not outside, but deep within the oral and written sources revered by each religious group: what we label the “hearth” around which group members gather.

Claim #6: My sixth and final claim is that we have on-the-ground evidence that Hearth-to-Hearth value studies can really work to draw members of opposing groups into deep discussion and negotiation. One illustration draws on the results of “Scriptural Reasoning”: a 25 yr. effort to draw very religious Muslims, Jews, and Christians (and more recently members of Asian religions), into shared study of their very different scriptural texts and traditions.

Dr. Peter Ochs is Edgar Bronfman Professor of Modern Judaic Studies at the University of Virginia, where he also directs religious studies graduate programs in “Scripture, Interpretation, and Practice,” an interdisciplinary approach to the Abrahamic traditions. He is cofounder of the (Abrahamic) Society for Scriptural Reasoning and the Global Covenant of Religions (an NGO devoted to engaging governmental, religious, and civil society agencies in comprehensive approaches to reducing religion-related violent conflicts). He directs the University of Virginia research Initiative in Religion, Politics, and Conflict. Among his publications are 200 essays and reviews, in the areas of Religion and Conflict, Jewish philosophy and theology, American philosophy, and Jewish-Christian-Muslim theological dialogue. His many books include Another Reformation: Postliberal Christianity and the Jews; Peirce, Pragmatism and the Logic of Scripture; The Free Church and Israel’s Covenant and the edited volume, Crisis, Call and Leadership in the Abrahamic Traditions.